…

A commercial aircraft silhouette is immediately identifiable. The long, thin fuselage, wide wings, and large tail; in signage terms it signifies an airport in most countries around the world.

But sign makers could be about to win a new contract, because the next generation of aircraft might not look like this at all. Under increasing pressure for greater efficiency and environmental performance, aircraft manufacturers may have to throw away the rule book to come up with something completely different.

New technology is not the only driver. According to an Airbus report, 72% of traffic operates through 114 airports -and that situation will only worsen in the years ahead. Dealing with congested gateways will be vital in future design.

Continued demand for an improved cabin experience also has to be taken into consideration, as does the fact that travelers will get older in some markets and younger in others, in line with world demographics. Underpinning all of this is aviation’s goal of halving its net carbon emissions by 2050.

The hybrid wing body design has become perhaps the best known of new ideas. A Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) research team used this concept as part of a NASA initiative to find next-generation aeronautical technologies.

The MIT H series is designed to replace widebody aircraft and would burn far less fuel, as well as reducing CO2 and nitrogen oxide emissions. A larger fuselage provides forward lift and eliminates the need for a tail, while the hybrid wing body design generates improved aerodynamics. Importantly, the design allows for a radical rethink of propulsion systems, and exactly what the engine could feature is now under evaluation by the research team.

Further into the future, an aircraft that could reconfigure its aerodynamic surfaces -such as spoilers, ailerons, and flaps- is not inconceivable. This ‘morphing’, which is comparable to what a bird instinctively does in flight, would optimize performance during each element of the flight profile.

Inside the cabin, passengers might be seated facing one another, which would increase aircraft capacity. Low‑cost carrier Ryanair has even gone as far as suggesting that passengers could stand up on short-haul flights.

Giving aircraft this level of revamp isn’t easy, however. Moving a new design from an initial concept and into commercial flight is a complicated process, and one that is getting more difficult by the day. Innovation takes time and money.

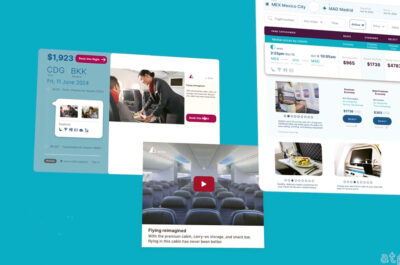

Boeing’s original idea for a new aircraft in the late 1990s was the Sonic Cruiser. But 9/11 upset the market and airlines became increasingly focused on efficiency gains at subsonic speed. Sonic Cruiser technology was adapted to a more conventional frame, and the Boeing board of directors finally granted authority to offer the 787 for sale in late 2003. All Nippon Airways became the launch customer a year later, but delays mean the first delivery is not scheduled until the third quarter of 2011.

“To develop a new product and bring it to the market is a challenge for everyone,” says Reiko Iechika, Manager of Branding at Mitsubishi Aircraft Corporation.

This has led to accusations of so-called specification creep -a succession of minor advances that forever delay radical new designs. The announcement of the A320neo, which is essentially the A320 with new engines, lends support to the argument.

Manufacturers assert there are two main reasons for this phenomenon. One is the enormous development costs involved. It is estimated that about $10 billion is needed to bring a new narrowbody model to market. Second, new technologies must warrant complete overhauls. If there isn’t a game-changing technology ready to be implemented then there is no need for a game changing design.

Despite the production challenges, airlines clearly demand the efficiencies that new aircraft bring. About 25,000 passenger aircraft, valued at more than $2.9 trillion, are expected to be delivered in the next 20 years. Ten thousand will replace older, less eco efficient aircraft, and some 15,000 will be for growth. It means the world’s fleet will total about 29,000 in 2030. Many of these will be new designs not flying in today’s market.